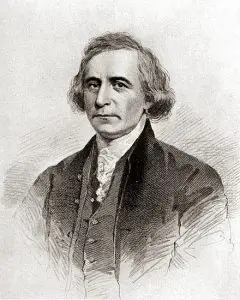

Philip [Morin] Freneau fulfilled the dream of his wine merchant father, Pierre Fresneau (old spelling) when he entered the Class of 1771 to prepare for the ministry. Well versed in the classics in Monmouth County under the tutelage of William Tennent, Philip entered Princeton as a sophomore in 1768, but the joy of the occasion was marred by his father’s financial losses and death the year before. In spite of financial hardships, Philip’s Scottish mother believed that her oldest of five children would graduate and join the clergy. Though he was a serious student of theology and a stern moralist all his life, Freneau found his true calling in literature. As his roommate and close friend James Madison recognized early, Freneau’s wit and verbal skills would make him a powerful wielder of the pen and a formidable adversary on the battlefields of print. Freneau soon became the unrivaled “poet of the Revolution” and is still widely regarded as the “Father of American Literature”.

Philip [Morin] Freneau fulfilled the dream of his wine merchant father, Pierre Fresneau (old spelling) when he entered the Class of 1771 to prepare for the ministry. Well versed in the classics in Monmouth County under the tutelage of William Tennent, Philip entered Princeton as a sophomore in 1768, but the joy of the occasion was marred by his father’s financial losses and death the year before. In spite of financial hardships, Philip’s Scottish mother believed that her oldest of five children would graduate and join the clergy. Though he was a serious student of theology and a stern moralist all his life, Freneau found his true calling in literature. As his roommate and close friend James Madison recognized early, Freneau’s wit and verbal skills would make him a powerful wielder of the pen and a formidable adversary on the battlefields of print. Freneau soon became the unrivaled “poet of the Revolution” and is still widely regarded as the “Father of American Literature”.

Although Freneau had produced several accomplished private poems before college, it was the intense experience of pre-Revolutionary-War Princeton that turned the poet’s interest to public writing. Political concerns led Madison, Freneau, and their friends Hugh Henry Brackenridge and William Bradford, Jr., to revive the defunct Plain Dealing Club as the American Whig Society. Their verbal skirmishes with the conservative Cliosophic Society provided ample opportunities for sharpening Freneau’s skills in prose and poetic satire. Charged with literary and political enthusiasm, Freneau and Brackenridge collaborated on a rollicking, picturesque narrative, Father Bombo’s Pilgrimage to Mecca in Arabia, which presents comic glimpses of life in eighteenth-century America. This piece, recently acquired by Princeton and published by the University Library (1975), may well be the first work of prose fiction written in America.

During their senior year Freneau and Brackenridge labored long on another joint project to which Freneau contributed the greater share. Their composition was a patriotic poem of epic design, “The Rising Glory of America”, a prophecy of a time when a united nation should rule the vast continent from the Atlantic to the Pacific. At the commencement exercises of September 1771, Brackenridge read this poem to a “vast concourse of the politest company”, gathered at Nassau Hall. The poem articulated the vision and fervor of a young revolutionary generation.

Freneau’s life after Princeton was one of change and conflict. He tried teaching and hated it. He spent two more years studying theology, but gave it up. He felt a deep obligation to perform public service, and his satires against the British in 1775 were written out of fervent patriotism. At the same time he distrusted politics and had a personal yearning to escape social turmoil and war. The romantic private poet within him struggled against his public role. Thus, paradoxically, in 1776 the “poet of the revolution” set sail for the West Indies where he spent two years writing of the beauties of nature and learning navigation. Suddenly in 1778, he returned to New Jersey and joined the militia and sailed the Atlantic as a ship captain. After suffering for six weeks on a British prison ship, he poured his bitterness into his political writing and into much of his voluminous poetry of the early 1780s.

By 1790, at the age of thirty-eight, with two collections of poetry in print and a reputation as a fiery propagandist and skillful sea captain, Freneau decided to settle down. He married Eleanor Forman and tried to withdraw to a quiet job as an assistant editor in New York. But politics called again. His friends Madison and Jefferson persuaded him to set up his own newspaper in Philadelphia to counter the powerful Hamiltonian paper of John Fenno. Freneau’s National Gazette upheld Jefferson’s “Republican” principles and even condemned Washington’s foreign policy. Jefferson later praised Freneau for having “saved our Constitution which was galloping fast into monarchy”, while Washington grumbled of “that rascal Freneau” — an epithet that became the title of Lewis Leary’s authoritative biography (1949).

After another decade of feverish public action, Freneau withdrew again in 1801, when Jefferson was elected president. He retired to his farm and returned occasionally to the sea. During his last thirty years, he worked on his poems, wrote essays attacking the greed and selfishness of corrupt politicians, and sold pieces of his lands to produce a small income. He discovered that he had given his best years of literary productivity to his country, for it had been in the few stolen moments of the hectic 1780’s that he found the inspiration for his best poems, such as “The Indian Burying Ground” and “The Wild Honey-Suckle”, a beautiful lyric which established him as an important American precursor of the Romantics.

Most students of Freneau’s life and writing agree that he could have produced much more poetry of high literary merit had he not expended so much energy and talent for his country’s political goals. In a way, though, he had fulfilled his father’s hopes for him, for he had devoted his life to public service as a guardian of the morals of his society and as a spokesman for the needs of its people.