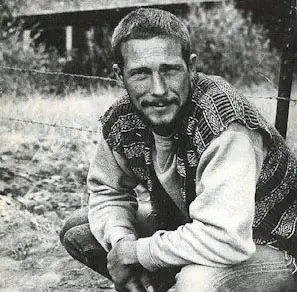

Gary Snyder (born May 8, 1930) is an American poet (often associated with the Beat movement) and an environmental activist who is frequently described as the ‘laureate of Deep Ecology’; both reflecting his studies of Buddhist spirituality and nature. Snyder is also a social critic whose views have shared something in common with Lewis Mumford, Aldous Huxley, Karl Hess, and Aldo Leopold.

Gary Snyder (born May 8, 1930) is an American poet (often associated with the Beat movement) and an environmental activist who is frequently described as the ‘laureate of Deep Ecology’; both reflecting his studies of Buddhist spirituality and nature. Snyder is also a social critic whose views have shared something in common with Lewis Mumford, Aldous Huxley, Karl Hess, and Aldo Leopold.

Snyder was born in San Francisco, California, but his family, impoverished by the Great Depression, moved to Washington when he was two and to Portland, Oregon ten years later. During the ten childhood years in Washington, Snyder become aware of the presence of Coast Salish people and developed an interest in American Native peoples in general and their traditional relationship with nature.

In 1947, he started attending Reed College as a scholarship student. Here he met, and for a time roomed with, Philip Whalen and Lew Welch. At Reed, Snyder published his first poems in a student journal. He also spent at least one summer working as a seaman. In 1951, he graduated with a BA in Anthropology and literature and spent the summer working in forestry in Yosemite, experiences which formed the basis for his earliest published poems, later collected in the book Riprap. Snyder had also encountered the basic ideas of Buddhism and, through its arts, some of the Far East’s traditional attitudes toward nature. Going on to Indiana University to study anthropology (where Snyder also practiced self-taught Zen meditation), he left after a single semester to return to San Francisco and to ‘sink or swim as a poet’.

Back in San Francisco, Snyder lived with Whalen, who shared his growing interest in Zen Buddhism. In 1953, he enrolled with the University of California, Berkeley to study Oriental culture and languages. Snyder continued to spend summers working in the forests, as a logger or as lookout in forest parks and spent some months in 1955 living in a cabin in Mill Valley with Jack Kerouac. It was also at this time that Snyder was an occasional student at the American Academy of Asian Studies, where Saburo Hasegawa and Alan Watts, among others, were teaching. This period provided the materials for Kerouac’s novel The Dharma Bums. As the large majority of people in the Beat movement had urban backgrounds, writers like Allen Ginsberg and Kerouac found Snyder, with his backcountry and manual-labor experience and interest in things rural, a refreshing and almost exotic individual. Lawrence Ferlinghetti later referred to Snyder as ‘the Thoreau of the Beat Generation’.

That same year, after Snyder met with Ginsberg, the latter having sought Snyder out on the recommendation of Kenneth Rexroth, Snyder performed at the famous poetry reading at the Six Gallery in San Francisco (October 13, 1955) that heralded what was to become known as the San Francisco Renaissance. This also marked Snyder’s first involvement with the Beats, although he was not a member of the original New York circle, but rather entered the scene through an association with Kenneth Rexroth. As recounted in Kerouac’s Dharma Bums, even at age 25 Snyder felt he could have a role in the fateful future meeting of West and East. Snyder’s first book, Riprap, which drew on his experiences as a forest lookout and on the trail crews in Yosemite, was published in 1959.

Independently, a number of the Beats such as Philip Whalen had become interested in Zen, but Snyder was one of the more serious scholars of the subject among them. He, in fact, became a trainee, spending most of the period between 1956 and 1968 in Japan studying Zen first at Shokoku-ji and later in the Daitoku-ji monastery in Kyoto. His previous study of written Chinese assisted his immersion in the Zen tradition (with its roots in Tang Dynasty China) and enabled him to take on certain professional projects while he was living in Japan. Eventually, he decided not to become a monk and to return to the United States to turn the ‘wheel of the dharma’.

During this time, he published Myths & Texts (1960) and Six Sections from Mountains and Rivers Without End (1965). (This last was the beginning of a project that he was to continue working on until the late 1990s.) Much of Snyder’s poetry expresses experiences, environments, and insights involved with the work he has done for a living – logging, fire lookout, steam-freighter laboring, translation of texts, carpentry, and life on-the-road presenting his poetry.

Ever the participant-observer, during his years in Japan Snyder not only immersed himself in Zen practice in monasteries but also was initiated into Shugendo, a form of ancient Japanese animism. (See also Yamabushi.) As well, in the early ’60s he travelled for some months through India.

In the late 1960s and after, the content of Snyder’s poetry increasingly has to do with family, friends, and community. He continued to publish poetry throughout the 1970s, much of it reflecting his re-immersion in life on the American continent and his involvement in the re-inhabitation (or back to the land) movement in the Sierra Nevada mountains of Northern California. His 1974 book Turtle Island, named for the aboriginal name for the North American continent won the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry. He also wrote a number of essays outlining his views on poetry, culture, and the environment. Many of these were collected in Earth House Hold (1969), The Old Ways (1977), The Real Work (1980), A Place in Space (1995), and The Gary Snyder Reader (1999). In 1978, Snyder published He Who Hunted Birds in His Father’s Village: The Dimensions of a Haida Myth, based on his Reed thesis.

In 1985, Snyder became a professor in the writing program at the University of California, Davis. Here he began to influence a new generation of authors interested in writing about the Far East, including novelist Robert Clark Young.

As Snyder’s involvement in environmental issues and his teaching grew, he seemed to move away from poetry for much of the 1980s and early 1990s. However, in 1996 he published the complete Mountains and Rivers Without End, which, in its mixture of the lyrical and epic modes celebrating the act of inhabitation on a specific place on the planet, is both his finest work and a summation of what a re-inhabitory poetic stands for.

Along the way, Gary Snyder was awarded the American Poetry Society Shelley Memorial Award (1986) and inducted into the American Academy of Arts and Letters (1987).